How Location Intelligence is playing a key role in tackling the Covid-19 pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic has seen huge numbers of people poring over maps and graphs looking for more information about the spread of and trends in the viral outbreak. Hundreds of organisations and individuals have set up dashboards in recent weeks. These typically combine graphs and maps and draw their data from a wide range of sources. Probably the most widely known global dashboard is from Johns Hopkins University, based in Maryland in the US. In Ireland, the Department of Health launched their dashboard, based on the Ordnance Survey’s GeoHive platform, on Wednesday 25th March. While dashboards are an important component of a health strategy that sets out to monitor and communicate information about Covid-19, understanding how the outbreak has spread from its origin and continues to move through the population is hugely important. Here are 6 ways that Location Intelligence is assisting health authorities manage the outbreak.

1. Contact Tracing

In the early stages of the outbreak the R0 for Covid-19 in Ireland was estimated to be over 3.0, illustrating just how contagious it is, with 10 iterations of contact reaching 59,000 people compared to the seasonal flu (R0 = 1.4) which could see only 14 people exposed after the same number of iterations. Thankfully the R0 has now reduced to between 0.5 and 0.8 after one month of restrictions. Keeping the R0 below 1 is the central task for the Irish health service and contact tracing is a key component for health service professionals.

Contact tracing methods vary widely by country. In Ireland the official Covid-19 case form contains an entry for Eircode, which allows the health service identify the exact location where the case lives and works.

South Korea has perhaps the most detailed contact tracing program, with websites and apps revealing detailed movement data for people who have tested positive. One such app, Corona-100m, alerts users if they are within 100m of the tracked whereabouts of a coronavirus patient and has been downloaded over 1 million times.

In China where the government has close surveillance on the local population there is an example of a ‘close contact detector’ app, which notifies users if they have shared a classroom, workplace, train carriage or residence with a confirmed case. In Taiwan the government is using geofencing techniques to ensure that those who are in quarantine remain at their home address. The Singapore government launched TraceTogether on Friday 20th March and it was in use by 12.5% of the population just 4 days later. This app uses Bluetooth to establish if app users have been in close confines with each other. Should an app user test positive, health professionals can notify other app users which the symptomatic person was in contact with. However after one month penetration of this app has stalled at about 19% of the population of Singapore, far below the level required to ensure success. The recent upswing in the number of cases in that country attests to this.

In Europe, the UK, and US, governments are seeking location data from mobile phone operators to track the outbreak and assist with contact tracing, however this has raised a range of privacy concerns.

It is possible to gather potentially useful location data from coronavirus patients without installing specialised apps or gathering data from mobile operators. Many mobile map apps such as Google Maps maintain a list of visited locations and travel routes used if the phone owner has opted in to storing this data. This data can be loaded into desktop mapping applications, such as Mapinfo for analysis, however gathering this data for a large section of the public would raise legitimate privacy concerns.

One year of location data recorded by Google Maps for the author.

The range of contact tracing methods used across Europe and Asia reveals differing attitudes towards the privacy of personal data. Many European citizens would balk at the concept of sharing such personal data with health authorities and may reasonably expect GDPR to prevent what they may regard as an invasion of privacy. It should be noted however that the GDPR has exemption clauses for National Security.

2. Movement

The world is a much more connected place than it was during the 1918 Flu Pandemic. Numerous models of the Covid-19 outbreak look at connectivity data, such as airline flight patterns, to estimate the flow of the infection from its origin point.

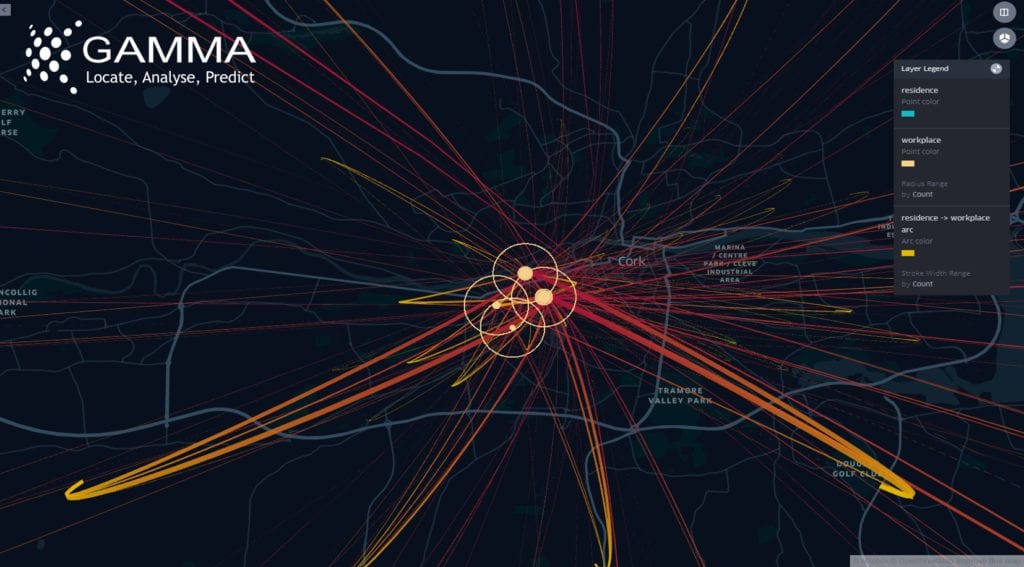

In Ireland commuter flow data is available from the Census, which makes available aggregated data for flows into and out of areas. This can be useful at the early stages of outbreak monitoring before travel restrictions disrupt regular commute patterns. The data is also useful post-pandemic as it can be used to assess the connectedness of areas that might be at risk.

Commuter flow to Cork City Centre. Data: CSO, Mapping: Gamma

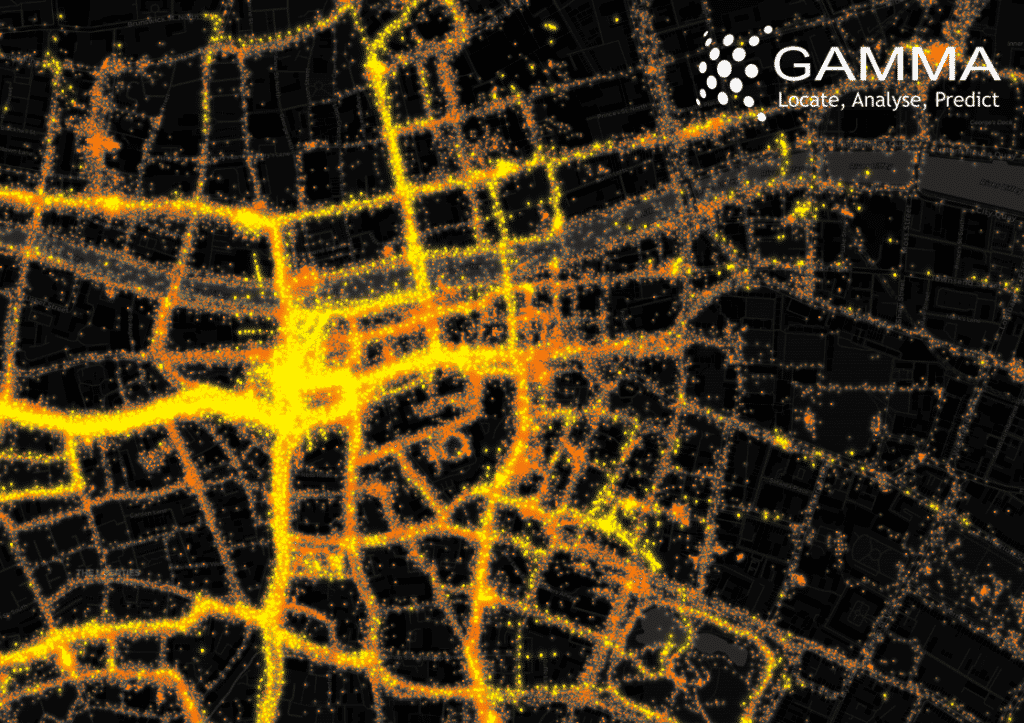

There are a number of commercial data providers for real-time road traffic data, including TomTom, HERE, Mapbox and others. This data is generated by apps, including sat-nav apps in vehicles, and can show the real-time impact of national shutdowns. In the case of Dublin, traffic on the 24th March was 44% below normal, one month later it is even further reduced.

Movement can also be estimated from non-traditional sources, such as seismometers. The 23rd April update from the Irish Department of Health included seismic data from the Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies which showed a large and sustained reduction in seismic noise that corresponds with the shutdown announced a month earlier.

3. Mapping vulnerable population

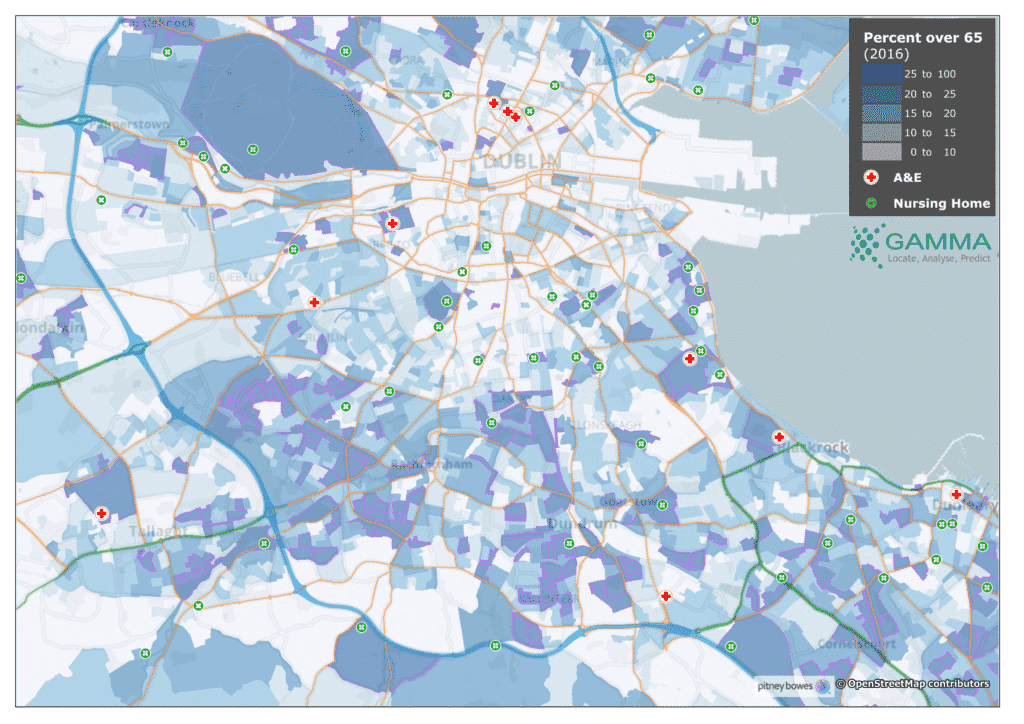

Current research is showing that older age groups are more prone to developing serious cases of Covid-19. By analysing Census data at the very detailed Small Area level (there are 18,644 Small Areas in Ireland) locations of where these demographics are more prevalent can be mapped. The Irish census also collects self reported general health, with respondents rating their own health on a 5 point scale from very good to very bad. Combining this with the demographics may show areas that are more vulnerable to severe cases of Covid-19. Census data also records the number of people living in communal establishments such as nursing homes, prisons and direct provision centres which are also especially vulnerable to outbreaks.

Areas in Dublin City shaded by proportion of persons aged over 65 in 2016, Major hospitals and Nursing Homes also shown

4. Air quality monitoring

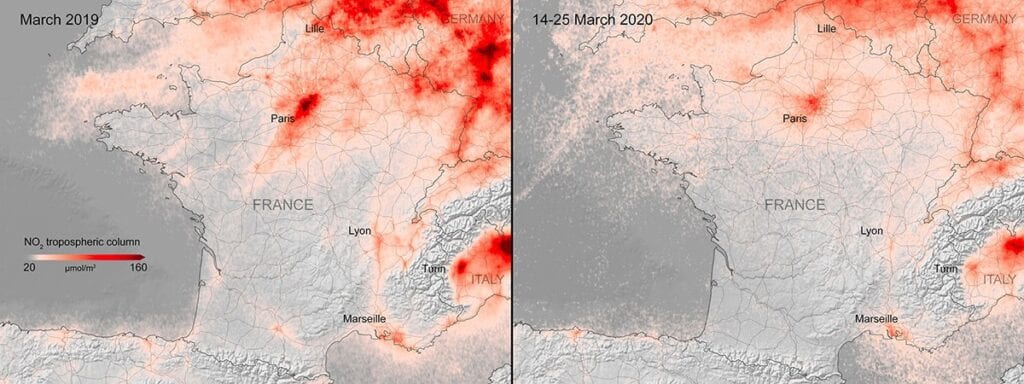

There is some early research that hints at possible connections between Covid-19 severity and poor air quality, particularly with particulate matter which is measured as PM10 and PM2.5 (diameter of particles less than 10 or 2.5 micrometres respectively). It should be noted that any connection between air quality and susceptibility to Covid-19 is unproven. Air Quality monitoring is one of the core elements of the EU’s Copernicus program which is composed of a constellation of monitoring satellites, associated ground stations and data management and publishing systems. The data from the Copernicus program is used to monitor the global environment, from changes in land use and extents of flood events to tracking weather systems and assessing soil quality and agricultural outputs. Recent analysis of Air Quality across Europe has shown a measurable decrease in pollutants, notably Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2), since the lockdown in Northern Italy.

Nitrogen dioxide concentrations over France. Credits: contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2019-20), processed by KNMI / ESA

5. Standard LI Applications

Beyond mapping and tracing the Covid-19 outbreak, Location Intelligence has a range of other roles to play. Ireland like many other countries has rapidly rolled out a testing infrastructure. Selecting the locations for these and defining their catchments is a classic use case for Geographic Information Systems. Allied to this are resource locators, where members of the public can query publicly available data to find their nearest pharmacy, doctor or hospital, with apps offering turn-by-turn navigation. Health authorities can use these for emergency and resource planning, with the current status of nearby medical facilities available to staff.

6. Mapping the recovery

Covid-19 has already had a severe impact on the global economy and the impact on Ireland will play out over the coming months. Ireland’s business landscape will be very different at the end of 2020 compared to the start of the year. These changes will be particularly visible on our main streets, where some retailers will struggle to recover from the economic shock, while others will thrive. Parts of the country more dependent on tourism may take longer to recover than others. Data that tracks and monitors these changes is available and will be increasingly valuable once the recovery gets underway.

Conclusion

Location Intelligence has a key role to play in understanding, tracking, planning and resolving the Covid-19 outbreak. Web based tools, real-time information and open data sharing and interoperability are the drivers as we seek to bring the outbreak under control and learn lessons that will help to ensure that any future outbreaks are dealt with more effectively and will a lower cost of life and reduced social and economic impact.

@ 2020 Gamma.ie by Richard Cantwell

About Gamma

Gamma is a Location Intelligence (LI) solutions provider; we integrate software, data and services to help our clients reduce risk through better decision-making. Gamma was established in 1993 and was the first company to develop LI for the private sector in Ireland. The company has expanded to become a global provider of cloud-hosted LI systems, micro-marketing solutions and related services.

About Richard Cantwell

Richard is the Senior GIS Consultant at Gamma and has over 25 years of experience managing and delivering GIS projects in Ireland, the UK and Internationally. Recognised as a thought leader in the industry, Richard is particularly interested in using spatial data to gain insight, support decisions and improve outcomes for clients. Richard is also a part-time lecturer in the TUD School of Surveying and Construction Management and is the Vice-President of the Irish Organisation for Geographic Information (IRLOGI).